Bas Châtel, Rick Quax, Vitor V. Vasconcelos, and colleagues published a study in Scientific Reports that challenges the common view of loneliness as a purely individual experience, instead viewing it as a network-driven social phenomenon.

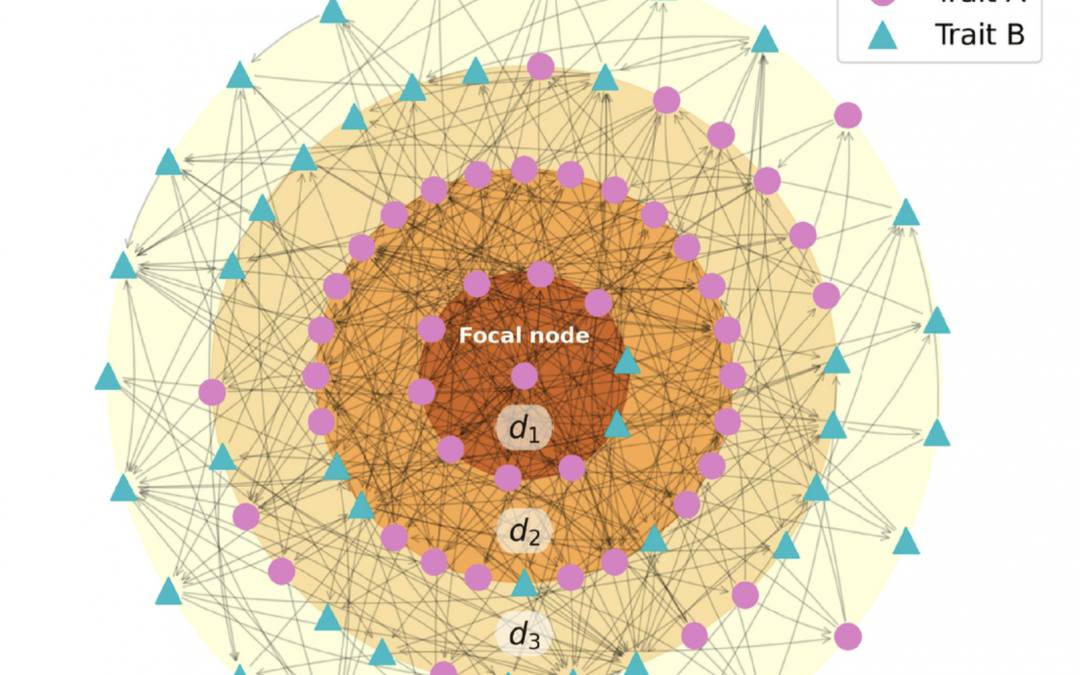

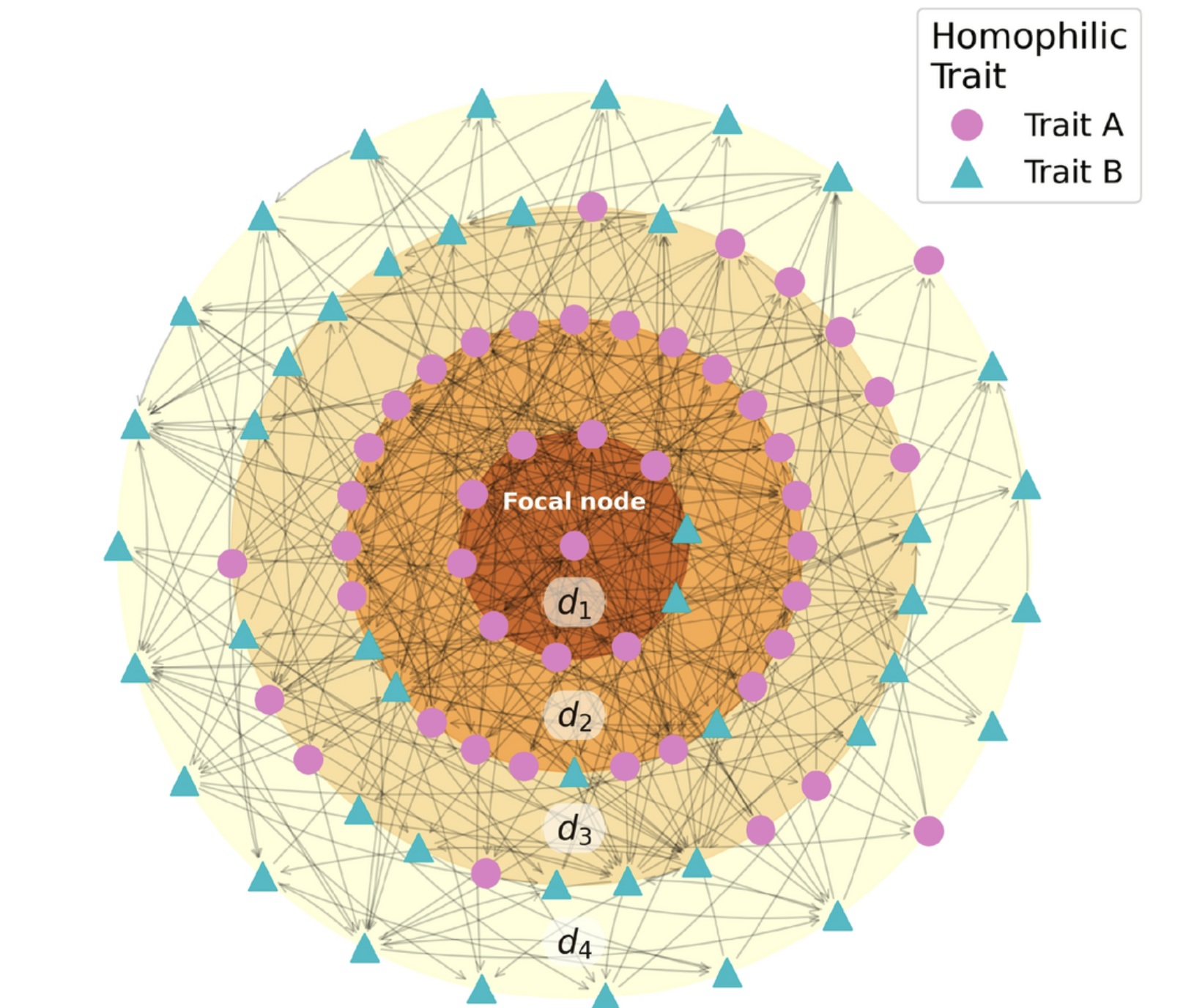

Loneliness is typically understood as the painful feeling of being socially disconnected, while desiring more connection. Although it is often viewed as an individual pathology, this study suggests that it is also shaped by the social environments in which people live. Using a computerized agent-based model, the researchers explored how feelings of loneliness can become concentrated in certain parts of a social network (i.e., it ‘clusters’) in social networks. Specifically, they tested two mechanisms that might explain why loneliness tends to cluster: homophily and induction. Homophily refers to the tendency for people with similar traits to form connections. Induction, on the other hand, describes how one person’s feelings or behaviors can influence those of others, effectively making emotions like loneliness contagious.

In their model, agents were given two dynamic characteristics: social energy and network connectivity. The study examined how loneliness spreads via three pathways: emotional contagion, where feelings align through exposure; behavioral contagion, where behaviors require reinforcement from multiple contacts; and cognitive contagion, where loneliness can self-activate (or de-activate) through internal feedback mechanisms like self-doubt or social withdrawal. Each pathway represents a different mechanism through which loneliness can spread in a network, and they could be acting at the same time and in different respective ratios.

A key finding was that high levels of homophily are essential for loneliness to cluster meaningfully in the network: when agents connected with others similar to themselves, distinct groups of lonely individuals emerged. In these high-homophily scenarios, the model also reproduced a well-documented phenomenon from real-world social networks known as the “three degrees of influence,” which suggests that a person’s emotional state can affect others up to three steps away in their network. Think: friends of friends of friends. Since all three types of social influence produce clustering, measuring loneliness clustering alone can not reliably help identify the reasons for its occurrence. However, all three pathways produce clustering in different ways over time, and studying these distinct dynamics further in a networked system context may help identify underlying real-world mechanisms more effectively.

The broader implication of the study is that loneliness should not be viewed only as a personal affliction but as a system-level issue, deeply embedded in the structure and dynamics of social relationships. The research introduces a new way of systematically simulating and analyzing loneliness within controlled network settings. At the same time, the authors acknowledge a limitation: because their model assumes the initial presence of homophily and does not simulate how networks are formed from individual choices, it cannot determine whether homophily alone provides sufficient evidence of loneliness clustering. This limitation, however, points to an important direction for future research.

Overall, the study calls for a shift in how loneliness is measured and understood. Rather than relying on static, individual-level assessments, researchers and policymakers should consider dynamic, network-based approaches. Such a shift could not only improve our understanding of how loneliness evolves but also inform more effective interventions, particularly those aimed at reconnecting isolated individuals and preventing the broader unraveling of social networks.

For more details, see https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-025-99057-x